Famous Leaders of the Greek War of Independence

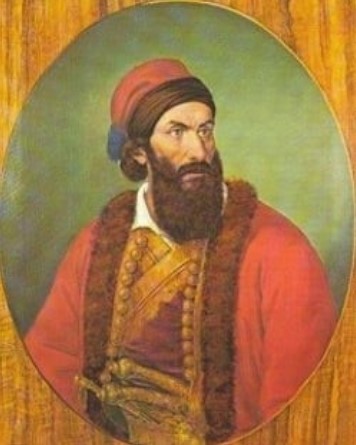

Odysseas Androutsos

Androutsos was born in Ithaca in 1788; however, his family was from the village of Livanates in Phthiotis prefecture.

His father was Andreas Androutsos, a klepht, and his mother was from Preveza.

After losing his father, Androutsos joined the Turkish army of Ali Pasha and became an officer; however, in 1818 he joined the Filiki Eteria, which was already plotting the liberation of the country through the Greek War of Independence.

In May 1821, Omer Vryonis, the commander of the Ottoman army, advanced with 8,000 men, after crushing the forces of the Greek resistance at the river of Alamana and killing Athanasios Diakos. The Ottomans then headed south into the Peloponnese to crush the Greek uprising.

Androutsos, with a band of about 100 men, took up a defensive position at an inn near Gravia, supported by Panourgias, Diovouniotis and their men. Vryonis attacked the inn but was pushed back with heavy casualties, as over 400 of his forces were killed. Finally, he was forced to ask for reinforcements and artillery but the Greeks managed to slip out before the reinforcements arrived.

Androutsos only lost two men in the battle and earned the title of Commander in Chief of the Greek forces in Roumeli.

Androutsos’ glory did not last long. In the following year, 1822, he was accused by political opponent Ioannis Kolettis of being in contact with the Turks and was stripped of his command.

Finally, in 1825, the revolutionary government placed him under arrest in a cave at the Acropolis of Athens. The new commander, Yiannis Gouras, who once was Androutsos’ second in command, had him executed on June 5, 1825.

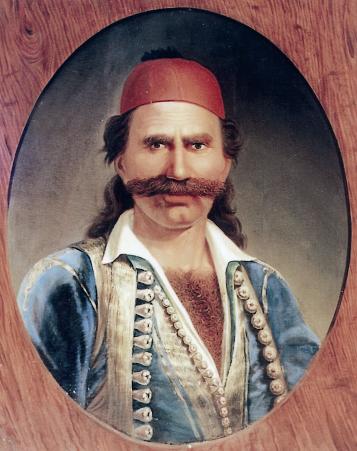

Markos Botsaris

Markos Botsaris, (born c. 1788, Soúli, Ottoman Empire [now in Greece]—died Aug. 21, 1823, Karpenisíon), an important leader early in the Greek War of Independence.

Botsaris’ early years were spent in the struggle between the Souliots of southern Epirus (Modern Greek: Íperos) and Ali Paşa, who had made himself ruler of Ioánnina (Janina) in Epirus in 1788. After Ali Paşa succeeded in capturing the Souliot strongholds in 1803, Botsaris and most of his surviving clansmen fled to Corfu (Kérkyra). He remained there for 16 years, serving in an Albanian regiment under French command. Strongly influenced by the European ideas of national independence and identity, he joined the patriotic society Philikí Etaireía in 1814.

Botsaris returned to Epirus with the Souliots in 1820 to join his former enemy Ali Paşa of Ioánnina in his revolt against the Turkish government and, after Ali Paşa was defeated, committed the Souliots to the Greek struggle for independence that had broken out in April 1821. After serving in the successful defense of the town of Missolonghi (Mesolóngion) during the first siege in 1822–23, he led a band of a few hundred Souliot guerrillas on the night of Aug. 21, 1823, in a bold attack on 4,000 Albanians encamped at Karpenisíon.

The Albanians, who formed the vanguard of a Turkish army advancing to join the siege, were routed, but Botsaris, who had proved to be one of the most promising commanders of the Greek forces, was killed. When Botsaris died, his command of the Souliots passed to his friend Lord Byron, who formed 50 of them into a personal bodyguard at Missolonghi.

Laskarina Bouboulina

Bouboulina born on May 11, 1771, was a woman who almost unbelievably became a Greek naval commander, and a true heroine of the Greek War of Independence.

She was born in a prison in Constantinople, but her origins were from the Arvanite community of the island of Hydra.

She was the daughter of a captain from the island, and had an extraordinarily unorthodox life for a woman at the time.

Boubloulina married twice, first to Dimitrios Yiannouzas and later to the wealthy ship owner and captain Dimitrios Bouboulis, taking his surname.

Bouboulina allegedly joined the Filiki Eteiria to fight for Greek freedom. She bought arms and ammunition at her own expense and brought them secretly to Spetses in her ships, to fight, as she stated, “for my nation.”

She also organized her own armed troops, composed of men from Spetses. She used most of her fortune to provide food and ammunition for the sailors and soldiers under her command.

On March 13, 1821 Bouboulina raised her own Greek flag raised on the mast of her ship, based on the flag of the Comnenus dynasty of Byzantine emperors. Bouboulina sailed with eight ships to Nafplio and began a naval blockade. Later she took part in the naval blockade and capture of Monemvasia and Pylos.

Bouboulina arrived at Tripolis in time to witness its fall on Sept. 11, 1821 and to meet general Theodoros Kolokotronis.

Two of their children, Eleni Boubouli and Panos Kolokotronis, later married. During the ensuing defeat of the Ottoman garrison, Bouboulina saved and freed most of the female members of the Sultan’s household.’She passed away on May 22, 1825.

Athanasios Diakos

Born in 1788 and passing away in April 24, 1821, Diakos served as a Greek military commander, and is widely considered to be one of the greatest military heroes of Greece.

Born Athanasios Nikolaos Massavetas in Phocis, in the village of Ano Mousounitsa, he was the grandson of a local klepht.

He was drawn to religion from an early age and was sent away by his parents to the Monastery of St. John The Baptist for his education.

He became a monk at the age of seventeen and, due to his devotion to faith and good temperament, was ordained a Greek Orthodox deacon not long afterward.

Local legend has it that while at the monastery, an Ottoman pasha paid a visit with his troops and was impressed by Diakos’ good looks. The young man took offense to the Turk’s remarks (and subsequent proposal) and killed the Turkish official.

Diakos was forced to flee into the nearby mountains and become a klepht. Soon afterward, he adopted the pseudonym “Diakos” (Deacon). He fought in several battles and his bravery was praised.

Diakos was captured by the Ottomans and was sentenced to death because he had killed many Ottoman fighters throughout the Greek War of Independence. His brutal execution by impalement also made him a martyr for the cause of Greek freedom.

Constantine Kanaris

Kanaris, who lived from 1793 (or 1795) to Sept. 2, 1877, was a Greek Prime Minister and admiral after he fought bravely in the Greek War of Independence.

Kanaris was born and grew up on the island of Psara, close to the island of Chios in the Aegean. He gained his reputation in June of 1822 in the Battle of Chios, when the Greek naval forces under his command destroyed the flagship of Turkish admiral Nasuhzade Ali Pasha (or Kara-Ali Pasha) in revenge for the Chios Massacre.

The admiral was holding a celebration aboard his ship. But meanwhile, Kanaris and his men managed to place a fire ship next to it. When the flagship’s powder store caught fire, all the men aboard were instantly killed in the gigantic explosion that resulted.

The Ottomans lost 2,000 men, including naval officers and common sailors, as well as Kara-Ali himself. Kanaris led further successful attacks against the Turkish fleet in Tenedos in November 1822 and on Samos in August 1824.

Kanaris was one of the few freedom fighters who had won the trust of Ioannis Kapodistrias, the first Head of State of independent Greece. Kanaris served as minister in various governments and then as Prime Minister in the provisional government, from March 11-April 11, 1844.

He served a second term, from Oct. 27, 1848 – Dec. 24, 1849, and as a Navy Minister in Mavrokordatos’ 1854 cabinet.

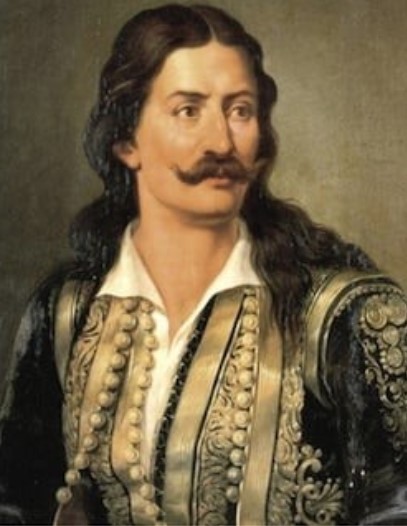

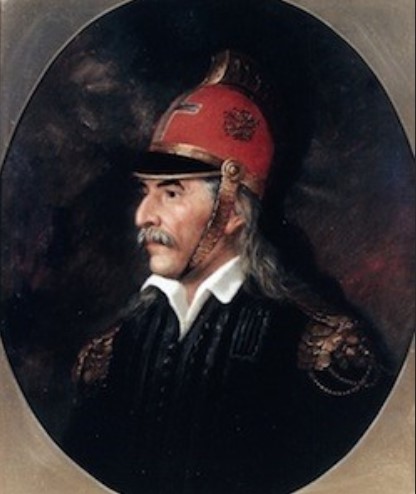

Geórgios Karaïskákis

Geórgios Karaïskákis, (born c. 1780, Mavrommati, Ágrafa, Epirus, Greece—died May 5, 1827, Athens), a klepht, or brigand chief, who played an important role in the Greek War of Independence. He is remembered both for his treachery and for his reckless courage.

Karaïskákis was a native of the district of Ágrafa in Epirus (Modern Greek: Íperos), a region known for its bandits and rebels. He served in the armatoli, or militia, and participated in the struggles between the Turkish authorities and the rebel Ali Paşa, pasha of Ioánnina (Janina). He served in Ali’s bodyguard (1808–20) but was on the Turkish side when the pasha was defeated and killed in February 1822. During the next few years he fought with the Greek patriots in western Greece but capitulated to the Turks whenever the struggle for independence seemed a poor risk.

Despite his treachery and selfish ambition, Karaïskákis was a brave warrior and one of the few Greek commanders the Turks actually feared. Pardoned by the Greek central government at Nauplia (Návplio), he put down a regional revolt in the Peloponnese (Pelopónnisos) in the autumn of 1824. In April 1826, as commander of the armatoli, he attempted to relieve the second siege of Missolonghi; his illness and the lack of discipline of the armatoli, however, prevented him from giving the Missolonghiots effective support in their attempt to break through Turkish lines, and few of the defenders survived. He was killed at the relief of the siege of the Acropolis in Athens (Athína) in 1827.

Theodoros Kolokotronis

Born on April 3, 1770 and dying on Feb. 4, 1843, Kolokotronis is the iconic leader of the Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire.

Kolokotronis was born in Ramavouni in Messenia into a family of rebels and grew up in Arcadia in the central Peloponnese. The Kolokotronis clan was powerful and respected in Arcadia in the eighteenth century.

The family had been in a constant state of war with the Ottomans since the sixteenth century, engaging in various acts of resistance.

From 1762 to 1806, seventy members of the greater Kolokotronis family were killed by the conquerors.

Kolokotronis’ greatest military success was the defeat of the Ottoman Army under Mahmud Dramali Pasha at the Battle of Dervenakia in 1822.

In 1825, he was appointed commander-in-chief of the Greek forces in the Peloponnese.

After the war, Kolokotronis became a supporter of Greece’s first governor, Ioannis Kapodistrias, and a proponent of an alliance with Russia.

When Kapodistrias was assassinated by a clan of Mani landowners on Oct. 8, 1831, Kolokotronis created his own administration in support of Prince Otto of Bavaria as king of Greece.

However, he later opposed Otto, and on June 7, 1834, he was charged with treason and sentenced to death. He was ultimately pardoned in 1835. Kolokotronis died in 1843 in Athens.

Yannis Makriyannis

Born Ioannis Triantaphyllou in 1797, this hero got his nickname from his tall figure, which literally translates to “Long John” in English.

Makriyannis was a Greek merchant, military officer, politician and author, best known today for his memoirs.

He joined the Greek uprising after being initiated into the Filiki Eteria secret society and was arrested after he was sent to the Peloponnese in March 1821 to observe developments there. He was arrested by the Turks and tortured after his mission became known.

During the war, he reached the rank of general and led his men to notable victories. After Greek independence was gained, he had a tumultuous public career, playing a prominent part in granting the first Constitution to the Kingdom of Greece. He was later sentenced to death but was pardoned.

Aside from being an invaluable source of historical and cultural information on the period, Makriyannis’ memoirs have also been called a “monument of Modern Greek literature,” as they are written in pure Demotic Greek. Indeed, its literary quality led Nobel laureate Giorgos Seferis to call Makriyannis one of the greatest masters of Modern Greek prose.

Manto Mavrogenous

This great lady, who lived from 1796 to 1848, was a heroine of the Greek War of Independence. A wealthy woman, she decided to spend her entire fortune for the Hellenic cause.

Under her encouragement, her European friends also contributed money and guns to the revolution.

Strangely, her contribution to the Greek revolution and her bravery are mostly praised by foreign historians, while Greeks underplayed the importance of her role.

Mavrogenous was born in Trieste, then part of the Austrian Empire, now part of Italy. She was the daughter of merchant — and Filiki Eteria member — Nikolaos Mavrogenis and Zacharati Chatzi Bati.

She was well-educated, multi-lingual and influenced by the Age of Enlightenment.

In 1809, she moved to Paros with her family, where she learned from her father that the Filiki Eteria was preparing what would become known as the Greek War of Independence.

Aléxandros Mavrokordátos

Aléxandros Mavrokordátos, (born Feb. 11, 1791, Constantinople [now Istanbul, Tur.]—died Aug. 18, 1865, Aegina, Greece), statesman, one of the founders and first political leaders of independent Greece.

The scion of a Greek Phanariot house (living in the Greek quarter of Constantinople) long distinguished in the Turkish imperial service, Mavrokordátos was secretary (1812–17) to Ioannis Karadja, hospodar (prince) of Walachia (now in Romania), and later went into exile with his master. In 1821, however, Mavrokordátos joined the revolutionaries in Greece who had just rebelled against the Turks; despite their suspicions of his Phanariot origins, he soon established himself as head of a regional government at Missolonghi, in western Greece. During December 1821–January 1822 he presided over the first National Assembly, at Epidaurus, and led in the drafting of a constitution.

Mavrokordátos was elected first president of the Hellenic republic, but the new government exercised little actual power, and he soon returned to Missolonghi, where he conducted a successful defense against the Turks (November 1822–January 1823). He represented the national government as governor-general (1823–25) at Missolonghi, receiving there Lord Byron, the famous English poet-partisan of the Greek cause. He later became the principal leader of the pro-English party, though he did not approve of the Greek demand for British protection (June–July 1825).

Ignored during the presidency of the Russophile Count Ioánnis Kapodístrias (1827–31), Mavrokordátos was appointed minister of finance (1832) and then prime minister (1833) under Greece’s first king, Otto. He later served as Greek envoy in Munich, Berlin, London, and finally Constantinople. Recalled from London by the king in February 1841 to head the foreign ministry, Mavrokordátos was soon charged with the formation of a government with himself as minister of the interior (July 1841); but his reformist administration quickly foundered in the face of royal absolutism, and on Aug. 20, 1841, he was forced to resign. After the revolution of 1843 he was again prime minister (1844, 1854–55).

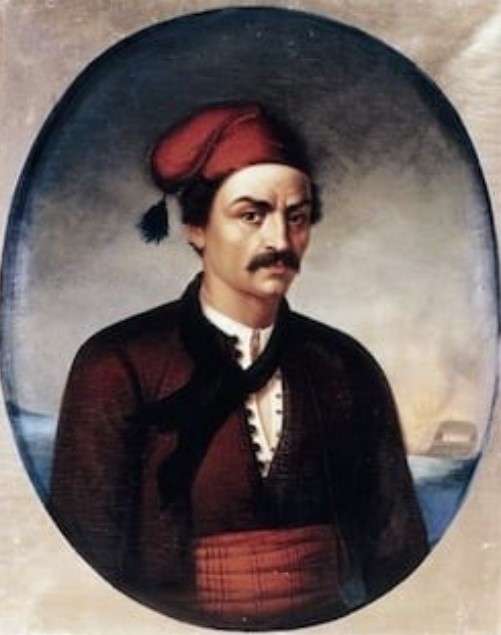

Andreas Miaoulis

Miaoulis, who was born on May 20, 1768 and died on June 24, 1835, was an admiral and politician who commanded Greek naval forces during the Greek War of Independence.

Miaoulis was born in Euboea to an Arvanite family and settled on the island of Hydra.

A corn merchant ship captain, he amassed great wealth and was chosen to lead the islands’ naval forces when they rose against the Ottoman Sultan.

Between May 1825 and January 1826, Miaoulis led the Greeks to victory in many skirmishes off Modon, Cape Matapan, Suda and Cape Papas.

Miaoulis died on June 24, 1835, in Athens. He was buried in Piraeus near the tomb of Themistocles, founder of the ancient Athenian Navy.

Papaflessas

Born Georgios Dimitrios Flessas in 1788, Papaflessas was a Greek patriot, a priest and a government official from the ancient Flessas family.

A member of the secret society Filiki Eteria, he took the nickname Papaflessas, literally meaning Priest Flessas.

He was one of twenty-eight children — and rumor has it that he was a womanizer like his father had been. He was ordained to the highest position of priesthood, Archimandrites, in 1819.

In 1823, Papaflessas was named Minister of Internal Affairs and Chief of Police by the government of Prince Alexandros Mavrocordatos under the name Gregorios Dikaios, the name he had when he was in Filiki Eteria.

As a Minister, he instituted many reforms, established the mail system and built schools in various towns.

Papaflessas created the title of Inspector General for schools and was the first one to establish a “political convictions certificate” to be given to the friends of the government. He also took part in many battles against the Turks.

Papaflessas sided with the government when civil war erupted in 1824. He took part in the campaign in Messenia and the rest of the Peloponnese to suppress the rebels against the government.

During the civil war, he was initially on Theodoros Kolokotronis’ side, but later switched due to his personal ambitions.

Papaflessas was killed during the Battle of Maniaki on May 20, 1825, fighting against the forces of Ibrahim Pasha.